Visual system

The visual system is the part of the central nervous system which enables organisms to see, as well as enabling several non-image forming photoresponse functions. It interprets information from visible light to build a representation of the surrounding world. The visual system accomplishes a number of complex tasks, including the reception of light and the formation of monocular representations; the construction of a binocular perception from a pair of two dimensional projections; the identification and categorization of visual objects; assessing distances to and between objects; and guiding body movements in relation to visual objects. The psychological manifestation of visual information is known as visual perception, a lack of which is called blindness. Non-image forming visual functions, independent of visual perception, include the pupillary light reflex (PLR) and circadian photoentrainment.

Contents |

Introduction

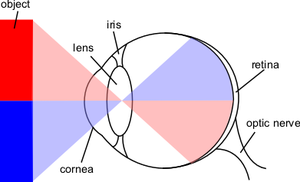

The image projected onto the retina is inverted due to the optics of the eye.

This article mostly describes the visual system of mammals, although other "higher" animals have similar visual systems. In this case, the visual system consists of:

- The eye, especially the retina

- The optic nerve

- The optic chiasma

- The optic tract

- The lateral geniculate body

- The optic radiation

- Visual cortex

- Visual association cortex

Different species are able to see different parts of the light spectrum; for example, bees can see into the ultraviolet,[1] while pit vipers can accurately target prey with their pit organs, which are sensitive to infrared radiation.[2]

History

In the second half of the 19th century, many motifs of the nervous system were identified such as the neuron doctrine and brain localisation, which related to the neuron being the basic unit of the nervous system and functional localisation in the brain, respectively. These would become tenets of the fledgling neuroscience and would support further understanding of the visual system.

The notion that the cerebral cortex is divided into functionally distinct cortices now known to be responsible for capacities such as touch (somatosensory cortex), movement (motor cortex), and vision (visual cortex), was first proposed by Franz Joseph Gall in 1810.[3] Evidence for functionally distinct areas of the brain (and, specifically, of the cerebral cortex) mounted throughout the 19th century with discoveries by Paul Broca of the language center (1861), and Gustav Fritsch and Edouard Hitzig of the motor cortex (1871).[3][4] Based on selective damage to parts of the brain and the functional effects this would produce (lesion studies), David Ferrier proposed that visual function was localised to the parietal lobe of the brain in 1876.[4] In 1881, Hermann Munk more accurately located vision in the occipital lobe, where the primary visual cortex is now known to be.[4]

Biology of the visual system

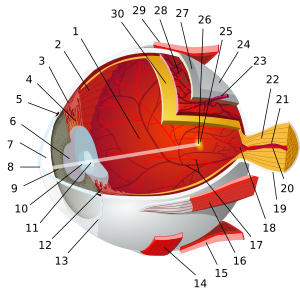

Eye

The eye is a complex biological device. The functioning of a camera is often compared with the workings of the eye, mostly since both focus light from external objects in the field of view onto a light-sensitive medium. In the case of the camera, this medium is film or an electronic sensor; in the case of the eye, it is an array of visual receptors. With this simple geometrical similarity, based on the laws of optics, the eye functions as a transducer, as does a CCD camera.

Light entering the eye is refracted as it passes through the cornea. It then passes through the pupil (controlled by the iris) and is further refracted by the lens. The cornea and lens act together as a compound lens to project an inverted image onto the retina.

Retina

The retina consists of a large number of photoreceptor cells which contain particular protein molecules called opsins. In humans, two types of opsins are involved in conscious vision: rod opsins and cone opsins. (A third type, melanopsin in some of the retinal ganglion cells (RGC), part of the body clock mechanism, is probably not involved in conscious vision, as these RGC do not project to the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) but to the pretectal olivary nucleus (PON).[5]) An opsin absorbs a photon (a particle of light) and transmits a signal to the cell through a signal transduction pathway, resulting in hyperpolarization of the photoreceptor. (For more information, see Photoreceptor cell).

Rods and cones differ in function. Rods are found primarily in the periphery of the retina and are used to see at low levels of light. Cones are found primarily in the center (or fovea) of the retina. There are three types of cones that differ in the wavelengths of light they absorb; they are usually called short or blue, middle or green, and long or red. Cones are used primarily to distinguish color and other features of the visual world at normal levels of light.

In the retina, the photoreceptors synapse directly onto bipolar cells, which in turn synapse onto ganglion cells of the outermost layer, which will then conduct action potentials to the brain. A significant amount of visual processing arises from the patterns of communication between neurons in the retina. About 130 million photoreceptors absorb light, yet roughly 1.2 million axons of ganglion cells transmit information from the retina to the brain. The processing in the retina includes the formation of center-surround receptive fields of bipolar and ganglion cells in the retina, as well as convergence and divergence from photoreceptor to bipolar cell. In addition, other neurons in the retina, particularly horizontal and amacrine cells, transmit information laterally (from a neuron in one layer to an adjacent neuron in the same layer), resulting in more complex receptive fields that can be either indifferent to color and sensitive to motion or sensitive to color and indifferent to motion.

The final result of all this processing is five different populations of ganglion cells that send visual (image-forming and non-image-forming) information to the brain:

- M cells, with large center-surround receptive fields that are sensitive to depth, indifferent to color, and rapidly adapt to a stimulus;

- P cells, with smaller center-surround receptive fields that are sensitive to color and shape;

- K cells, with very large center-only receptive fields that are sensitive to color and indifferent to shape or depth;

- another population that is intrinsically photosensitive; and

- a final population that is used for eye movements.

A 2006 University of Pennsylvania study calculated the approximate bandwidth of human retinas to be about 8960 kilobits per second, whereas guinea pig retinas transfer at about 875 kilobits.[6]

In 2007 Zaidi and co-researchers on both sides of the Atlantic studying patients without rods and cones, discovered that the novel photoreceptive ganglion cell in humans also has a role in conscious and unconscious visual perception.[7][8][9] The peak spectral sensitivity was 481 nm. This shows that there are two pathways for sight in the retina – one based on classic photoreceptors (rods and cones) and the other, newly discovered, based on photoreceptive ganglion cells which act as rudimentary visual brightness detectors.

Photochemistry

In the visual system, retinal, technically called retinene1 or "retinaldehyde", is a light-sensitive retinene molecule found in the rods and cones of the retina. Retinal is the fundamental structure involved in the transduction of light into visual signals, i.e. nerve impulses in the ocular system of the central nervous system. In the presence of light, the retinal molecule changes configuration and as a result a nerve impulse is generated.

Fibers to thalamus

Optic nerve

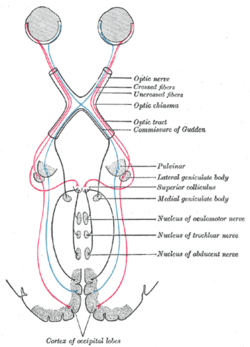

The information about the image via the eye is transmitted to the brain along the optic nerve. Different populations of ganglion cells in the retina send information to the brain through the optic nerve. About 90% of the axons in the optic nerve go to the lateral geniculate nucleus in the thalamus. These axons originate from the M, P, and K ganglion cells in the retina, see above. This parallel processing is important for reconstructing the visual world; each type of information will go through a different route to perception. Another population sends information to the superior colliculus in the midbrain, which assists in controlling eye movements (saccades)[10] as well as other motor responses.

A final population of photosensitive ganglion cells, containing melanopsin, sends information via the retinohypothalamic tract (RHT) to the pretectum (pupillary reflex), to several structures involved in the control of circadian rhythms and sleep such as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN, the biological clock), and to the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus (VLPO, a region involved in sleep regulation).[11] A recently discovered role for photoreceptive ganglion cells is that they mediate conscious and unconscious vision – acting as rudimentary visual brightness detectors as shown in rodless coneless eyes.[7]

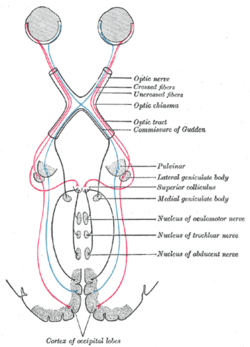

Optic chiasm

The optic nerves from both eyes meet and cross at the optic chiasm,[12][13] at the base of the hypothalamus of the brain. At this point the information coming from both eyes is combined and then splits according to the visual field. The corresponding halves of the field of view (right and left) are sent to the left and right halves of the brain, respectively, to be processed. That is, the right side of primary visual cortex deals with the left half of the field of view from both eyes, and similarly for the left brain.[10] A small region in the center of the field of view is processed redundantly by both halves of the brain.

Optic tract

Information from the right visual field (now on the left side of the brain) travels in the left optic tract. Information from the left visual field travels in the right optic tract. Each optic tract terminates in the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) in the thalamus.

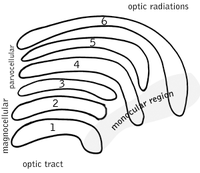

Lateral geniculate nucleus

The lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) is a sensory relay nucleus in the thalamus of the brain. The LGN consists of six layers in humans and other primates starting from catarhinians, including cercopithecidae and apes. Layers 1, 4, and 6 correspond to information from the contralateral (crossed) fibers of the nasal visual field; layers 2, 3, and 5 correspond to information from the ipsilateral (uncrossed) fibers of the temporal visual field. Layer one (1) contains M cells which correspond to the M (magnocellular) cells of the optic nerve of the opposite eye and are concerned with depth or motion. Layers four and six (4 & 6) of the LGN also connect to the opposite eye, but to the P cells (color and edges) of the optic nerve. By contrast, layers two, three and five (2, 3, & 5) of the LGN connect to the M cells and P (parvocellular) cells of the optic nerve for the same side of the brain as its respective LGN. Spread out, the six layers of the LGN are the area of a credit card and about three times its thickness. The LGN is rolled up into two ellipsoids about the size and shape of two small birds' eggs. In between the six layers are smaller cells that receive information from the K cells (color) in the retina. The neurons of the LGN then relay the visual image to the primary visual cortex (V1) which is located at the back of the brain (caudal end) in the occipital lobe in and close to the calcarine sulcus.

Optic radiation

The optic radiations, one on each side of the brain, carry information from the thalamic lateral geniculate nucleus to layer 4 of the visual cortex. The P layer neurons of the LGN relay to V1 layer 4C β. The M layer neurons relay to V1 layer 4C α. The K layer neurons in the LGN relay to large neurons called blobs in layers 2 and 3 of V1.

There is a direct correspondence from an angular position in the field of view of the eye, all the way through the optic tract to a nerve position in V1. At this juncture in V1, the image path ceases to be straightforward; there is more cross-connection within the visual cortex.

Visual cortex

The visual cortex is the most massive system in the human brain and is responsible for processing the visual image. It lies at the rear of the brain (highlighted in the image), above the cerebellum. The region that receives information directly from the LGN is called the primary visual cortex, (also called V1 and striate cortex). Visual information then flows through a cortical hierarchy. These areas include V2, V3, V4 and area V5/MT (the exact connectivity depends on the species of the animal). These secondary visual areas (collectively termed the extrastriate visual cortex) process a wide variety of visual primitives. Neurons in V1 and V2 respond selectively to bars of specific orientations, or combinations of bars. These are believed to support edge and corner detection. Similarly, basic information about color and motion is processed here.

Visual association cortex

As visual information passes forward through the visual hierarchy, the complexity of the neural representations increase. Whereas a V1 neuron may respond selectively to a line segment of a particular orientation in a particular retinotopic location, neurons in the lateral occipital complex respond selectively to complete object (e.g., a figure drawing), and neurons in visual association cortex may respond selectively to human faces, or to a particular object.

Along with this increasing complexity of neural representation may come a level of specialization of processing into two distinct pathways: the dorsal stream and the ventral stream (the Two Streams hypothesis,[14] first proposed by Ungerleider and Mishkin in 1982). The dorsal stream, commonly referred to as the "where" stream, is involved in spatial attention (covert and overt), and communicates with regions that control eye movements and hand movements. More recently, this area has been called the "how" stream to emphasize its role in guiding behaviors to spatial locations. The ventral stream, commonly referred as the "what" stream, is involved in the recognition, identification and categorization of visual stimuli.

However, there is still much debate about the degree of specialization within these two pathways, since they are in fact heavily interconnected.[15]

See also

- Echolocation

- Computer vision

- Memory-prediction framework

- Visual perception

- Visual modularity

References

- ↑ Bellingham et al. 1997, pp. 775–781

- ↑ Safer & Grace 2004, pp. 55–61.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Gross 1994, pp. 455–69

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Schiller 1986, pp. 1351–86

- ↑ Güler, A.D.; et al (May 2008), "Melanopsin cells are the principal conduits for rod-cone input to non-image-forming vision" (Abstract), Nature 453 (7191): 102–5, doi:10.1038/nature06829, PMID 18432195, PMC 2871301, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18432195?ordinalpos=3&itool=EntrezSystem2.PEntrez.Pubmed.Pubmed_ResultsPanel.Pubmed_DefaultReportPanel.Pubmed_RVDocSum, retrieved 2010-06-03.

- ↑ Calculating the speed of sight – being-human – 28 July 2006 – New Scientist

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Zaidi et al. 2007, pp. 2122–8

- ↑ Normal Responses To Non-visual Effects Of Light Retained By Blind Humans Lacking Rods And Cones

- ↑ Blind humans lacking rods and cones retain normal responses to nonvisual effects of light

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Nolte 2002, pp. 410–447

- ↑ Lucas, pp. 245–7

- ↑ al-Haytham 1021, p. 98

- ↑ Vesalius 1543

- ↑ Mishkin M, Ungerleider LG. (1982), "Contribution of striate inputs to the visuospatial functions of parieto-preoccipital cortex in monkeys.", Behav Brain Res. 6 (1): 57–77, doi:10.1016/0166-4328(82)90081-X, PMID 7126325.

- ↑ Farivar R. (2009), "Dorsal-ventral integration in object recognition.", Brain Res Rev. 61 (2): 144–53, doi:10.1016/j.brainresrev.2009.05.006, PMID 19481571.

Further reading

- al-Haytham (1021), Book of Optics, ISBN 9780292781498, http://books.google.com/?id=3VfY8PgmhDMC&pg=RA1-PA97&lpg=RA1-PA97&dq=al-haytham+visual+system, retrieved 2008-07-05: the Google books link shows Alhazen's sketch of optic nerve 522 years before Vesalius' engraving.

- Bellingham, J; Wilkie, SE; Morris, AG; Bowmaker, JK, Hunt,DM; Hunt, DM (1997), "Characterisation of the ultraviolet-sensitive opsin gene in the honey bee, Apis mellifera", European Journal of Biochemistry 243 (3): 775–781, doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.00775.x, PMID 9057845.

- Gross, Charles G. (1994-09-01), "How Inferior Temporal Cortex Became a Visual Area", Cereb. Cortex 4 (5): 455–469, doi:10.1093/cercor/4.5.455, PMID 7833649, http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/4/5/455, retrieved 2008-06-09

- Hubel, David H. (1989), Eye, Brain and Vision, New York: Scientific American Library.

- Lucas, R. J., S. Hattar, M. Takao, D. M. Berson, R. G. Foster, and K. W. Yau; S. Hattar, M. Takao, D. M. Berson, R. G. Foster, and K. W. Yau (2003), "Diminished Pupillary Light Reflex at High Irradiances in Melanopsin-Knockout Mice", Science 299 (5604): 245–247, doi:10.1126/science.1077293, PMID 12522249, http://stke.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/sci;299/5604/245.

- Marr, David (1982), Vision: A Computational Investigation into the Human Representation and Processing of Visual Information, San Francisco: W. H. Freeman.

- Nolte, John (2002), The Human Brain: An Introduction to Its Functional Anatomy. 5th Ed, St. Louis: Mosby, pp. 410–447.

- Rodiek, R.W. (1988), ""The Primate Retina"", "Comparative Primate Biology, Neurosciences (New York: A.R. Liss) 4. (H.D. Steklis and J. Erwin, editors.) pp. 203–278.

- Safer, AB; Grace, MS (2004-09-23), "Infrared imaging in vipers: differential responses of crotaline and viperine snakes to paired thermal targets", Behav Brain Res 154 (1): 55–61, doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2004.01.020, PMID 15302110.

- Schiller, P H (1986), "The central visual system", Vision research 26 (9): 1351–86, doi:10.1016/0042-6989(86)90162-8, ISSN 0042-6989, PMID 3303663, http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0042-6989(86)90162-8

- Schmolesky, Matthew, The Primary Visual Cortex, http://webvision.med.utah.edu/VisualCortex.html, retrieved 2005-01-01.

- Tovée, Martin J. (1996), An introduction to the visual system, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-48339-5 (References, pp. 180–198. Index, pp. 199–202. 202 pages.)

- Vesalius, Andreas (1543), De Humani Corporis Fabrica (On the Workings of the Human Body)

- Wiesel, Torsten; Hubel, David H. (1963), "The effects of visual deprivation on the morphology and physiology of cell's lateral geniculate body", Journal of Neurophysiology 26.

- Zaidi, FH; Hull, JT; Peirson, SN; Wulff, K; Aeschbach, D, Gooley JJ, Brainard GC, Gregory-Evans K, Rizzo JF 3rd, Czeisler CA, Foster RG, Moseley MJ, Lockley SW; Gooley, JJ; Brainard, GC; Gregory-Evans, K et al. (2007-12-18), "Short-wavelength light sensitivity of circadian, pupillary, and visual awareness in humans lacking an outer retina", Curr Biol. 17 (24): 2122–8, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.11.034, PMID 18082405

External links

- "Webvision: The Organization of the Retina and Visual System" – John Moran Eye Center at University of Utah

- VisionScience.com – An online resource for researchers in vision science.

- Journal of Vision – An online, open access journal of vision science.

- Hagfish research has found the “missing link” in the evolution of the eye. See: Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||